A presentation and discussion on the continuities and discontinuities between the world of sacred plants and that of psychedelic science. This talk focused on what psychedelic therapists and scientists can learn from ayahuasca shamanism, as well as critique some common misunderstandings around the notions of set, setting, and integration. How can we dialogue with Indigenous traditions, knowledge, and practices? How can we practice reciprocity with Indigenous people?

The author offered an overview of Chacruna Institute’s various projects and central mission to bridge ceremonial plant medicines and psychedelic science, and to place social sciences and culture at the center of the conversation. The hope is to contribute to the rewriting of mainstream psychedelic narratives and practices while advancing equity and access in psychedelic medicine.

Dr. Beatriz Caiuby Labate (Bia Labate) is a queer Brazilian anthropologist based in San Francisco. She has a Ph.D. in social anthropology from the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Brazil. Her main areas of interest are the study of plant medicines, drug policy, shamanism, ritual, and religion. She is Executive Director of the Chacruna Institute for Psychedelic Plant Medicines (http://chacruna.net, https://chacruna-la.org). She is Public Education and Culture Specialist at the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), and Adjunct Faculty at the East-West Psychology Program at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS). She is also co-founder of the Interdisciplinary Group for Psychoactive Studies (NEIP) in Brazil. She is author, co-author, and co-editor of 21 books, two special-edition journals, and several peer-reviewed articles.

Full Transcript:

[MUSIC PLAYING]

CHARLES STANG: Welcome. My name is Charles Stang, and I'm the director of the Center for the Study of World Religions here at Harvard Divinity School. Welcome to the six events in our yearlong series on psychedelics and the future of religion, a series co-sponsored by the Esalen Institute, the RiverStyx Foundation, and the Chacruna Institute for Psychedelic Medicines.

The next event in this series will be a lecture on Monday, March 22 from 3:00 to 4:30 PM. Please note that's not our usual time. And that is a lecture by Professor Wouter Hanegraaff from the University of Amsterdam, hence the earlier start time.

His lecture is entitled "Reasonably Irrational: Theurgy and the Pathologization of an Antigenic Experience." And it will continue the investigation begun with my interview with Brian [INAUDIBLE] regarding evidence for psychedelics in the ancient world. As always, the best way to keep abreast of this series and everything else we do at the center is to join our mailing list.

It is my great pleasure and privilege to welcome to the center Dr. Bia Labate. Dr. Labate is a queer Brazilian anthropologist based in San Francisco. She has a PhD in social anthropology from the State University of Campinas, Brazil. Her main areas of interest are the study of plant medicines, drug policy, Shamanism ritual, and religion.

She's executive director of the Chacruna Institute for Psychedelic Plant Medicine, as I mentioned, one of our co-sponsors. Thank you for that. And we're very proud to have them as co-sponsors for the series. She's also a public education and culture specialist at the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS. And she's adjunct faculty at the East-West Psychology Program at the California Institute of Integral Studies.

She's also the co-founder of the Interdisciplinary Group for Psychoactive Studies in Brazil. She's an author, co-author, and co-editor of 21 books, two special edition journals, and several peer-reviewed articles, and by several, I mean dozens.

This evening, Dr. Labate will be speaking about honoring the Indigenous roots of the psychedelic movement. Her representation will discuss the continuities and discontinuities between the world of sacred plants and that of psychedelic science.

It will focus on what psychedelic therapists and scientists can learn from ayahuasca shamanism as well as critique some common misunderstandings about the notions of set, setting, and integration. How can we dialogue with Indigenous traditions, knowledge, and practices? How can we practice reciprocity with Indigenous peoples?

She will offer an overview of Chacruna Institute's various projects and central mission, which is to bridge ceremonial plant medicines and psychedelic science and to place social sciences and culture at the center of the conversation. The hope is to contribute to the rewriting of mainstream psychedelic narratives and practices while advancing equity and access in psychedelic medicine.

So here is how this evening's event will unfold. Dr. Labate will deliver her lecture, and then we'll open it up to questions and comments. That's it. So once again, thank you all for joining us, and please join me in welcoming Dr. Bia Labate to the center. Bia, the floor is yours.

BIA LABATE: Hi, Charlie. Thank you. Thank you for the kind words. I'm going to share my screen here. If you bear with me one minute, I have prepared this PowerPoint. OK, hello, everybody. Thanks for being here today. I want to thank Harvard Divinity School for the invitation and for all the people that worked to make this happen.

My name is Bia Labate, and I'm speaking from San Francisco Bay Area, Ohlone territory, and I go by the pronouns she and her. And I'm very pleased to be here today. And Chacruna is a proud co-sponsor of the series. I'm going to start my presentation.

This presentation I will combine a bit my trajectory as an academic with my role as executive director of the Chacruna Institute for Psychedelic Plant Medicines. And I will give a little bit of some theoretical flights over papers and conversations that we have in the field of anthropology regarding plant medicine but also try to address some of the current interests of our non-profit in this field.

So our non-profit is dedicated to providing public education around psychedelic plant medicines. And we see as our main mission to create a bridge between the world of tradition, ritual, religion, ceremony, Indigenous people, and the emergent field of psychedelic assisted therapy and psychedelic science.

Also, it's part of our mission and central to us to promote equity, inclusion, diversity in the field of psychedelics, and we have been creating a lot of conversations, critical thinking about topics that often don't appear in mainstream conversations in the field of psychedelics.

So our work stands more or less in three main pillars. There's the pillar of education, and here I mean research, academic research, but also just public education. And I invite everybody to visit our site and learn about the "Chacruna Chronicles" where we publish some of this cutting edge ahead of the curve topics that are normally rejected in other forums.

But we're also engaged in creating community, and we have a series of events and conferences and other initiatives. And as I said, it's very central to us the topic of social justice, and we have been focusing on bringing the voices of women-- by the way, celebration and congratulations to all of us on the International Women's Day today.

More power to us and to all our descendants hopefully to bring a new world for the future female that are born after us. And so we're focusing on bringing the voices of queer people, women, people of color, Black people, Indigenous people, and voices from the global South into the mainstream psychedelic conversation.

I just want to give a little shout out. This is the Chacruna bush. The leaves of the bush [INAUDIBLE], it's a word in [INAUDIBLE] and our non-profit. This is one of the components that you brew ayahuasca with. So our non-profit is named after ayahuasca, and we consider that we are here to serve the plants and the people and the territories from where these plants come from. And all the work is in gratitude and honor to these plant and to these traditions and to the original people that brought this knowledge to us. So I just don't want us to forget.

There's a little baby Chacruna over there on the side. And also, just for you who don't know what Chacruna means, that's what it is, and that's how influential Chacruna ayahuasca is for many of us, inspiring us, making us dream, see, and above all, have many, many questions and many, many curiosities in this endless path into studying ayahuasca and plant medicines and all their benefits and challenges and paradoxes of globalization.

So here are some of the questions that I want to talk about today, and please bear with me. And also, remember that English is not my first language. And so maybe sometimes I say something wrong. Pity and mercy on me. We have seen colleagues get criticized for wrong choices of words. Please always remember when you're talking to non-native speakers that we are speaking a foreign language.

So what are the continuities and discontinuities between the world of sacred plants and that of psychedelic science? What can ayahuasca shamanism teach to psychedelic therapists? And then, we're going to revisit a bit the concepts of set, setting, and integration. And also, as psychedelics are medicalized, how do we incorporate dialogue with Indigenous tradition, knowledge, and practices?

How can we bridge the world of ceremony with that of psychedelic therapy? And what is the place of social sciences in the psychedelic conversation? Is there a place for it, and how important is it? And how can we be reciprocal towards Indigenous people?

All right, it's a lot of topics. Maybe I can cover all. I ask you all to be tolerant and open to maybe a few ideas that are a bit unconventional for some of you. And just try to listen and have an open attitude because I'm going to criticize some stereotypes and tropes and topics that appear frequently in the field of psychedelic medicine. So I hope you hear that with curiosity.

I just wanted to put this picture on. This picture was published in our peyote book, and it was part of the article from Dr. [INAUDIBLE]. And I also give my shout out to her. She's part of our team. And these are scientists that are attending a ceremony in Canada. And you can see there in one of the pictures is Humphry Osmond.

So I just want to start by saying that some of the regional scientists promoting the so-called psychedelic science emerged in the context of researchers sitting in tepees with Native Americans in Canada. It was when Humphry Osmond and Abraham Hoffer sat with the Native American group in Canada that they noticed that the Native American church was effective in treating alcoholism. That word, I never get it right. And they had the idea to try LSD as a treatment for alcoholics.

So I just want to make a disclaimer that this lecture will not make a historical overview of how Indigenous people have used traditionally plant medicines in different contexts in the Americas and elsewhere pointing to their numerous contributions, but rather, just make a general comment that this legacy is not really well acknowledged. And if we take some of this legacy seriously, what can we learn from it, and what can we do with it.

So I hope for those of you that were expecting more that other kind of lecture that this is not disappointing, but also, there's many other publications talking about this issue. So I really thought that this was going to be of more value for us here.

So moving forward, what do we get from now, and also as I say, appetizer overview of the larger topic. The very origin of the term psychedelics has a legacy from these scientists' experiences with Native Americans and curiosity about the rituals that accompanied their use. And we can give multiple examples, but to stick with one, Mescaline's molecular structure was identified by studying peyote, the main sacrament of the Native American church.

So Indigenous knowledge keepers have, in one way or another, informed the birth of the psychedelic movement and continue to do so. There's multiple evidence to this, but in my mind, and this is very important message, one shall remember that there is a continuity between what has been the shamanic use of psychedelic medicines or sacred plants or entheogens or other plant teachers, other terms that we use to designate this, and the underground settings where people use these substances therapeutically or in some kind of mixed hybrid rituals and the above ground from psychedelic assisted therapy.

So we didn't invent the wheel, and we didn't discover this out of the blue, and even for those that only like synthetic medicines, such as LSD and MDMA, and therefore, I think that we learned this in a laboratory, and therefore, we have nothing to do with Indigenous people, and unfortunately, we have seen a lot of prominent researchers claiming this kind of thing.

Even to those people, I claim that this is mistaken, and it doesn't properly acknowledge the historical roots of this movement. And in many, many ways, all of us are indebted to Indigenous peoples and their traditions and their knowledge when we are interested in these medicines.

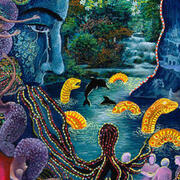

So I want to bring here the concept of plant teacher, which is a central concept that has been guiding a lot of conversations among anthropologists that study this kind of medicine. The picture that I chose to illustrate this is this beautiful painting by my wife, Clancy Kavnar, and it's the illustration of our book, the cover, Ayahuasca Shamanism in the Amazon and Beyond.

And there's a play of words with this title, Beyond the Amazon, but also, beyond into the invisible worlds, into the world of the ancestors. And to a lot of Indigenous people, ayahuasca is a direct gift. It was given to man, or it was men could learn about ayahuasca through the original snakes that have given this knowledge to us. So this illustration depicts this topic that is a theme that is common in many different [INAUDIBLE] traditions, but also other traditions regarding ayahuasca.

So what is the idea of a plant teacher or a spirit plant or master plant, plantas maestros in Spanish or plantas profesoras in Portuguese? And we have named a few books after these plants. [NON-ENGLISH] the ritual use of plants of power, [NON-ENGLISH] the ritual use of psychoactive plants in the Americas.

The idea of a plant teacher is that these plants are in fact beings. They have agency. They have intentionality. They are alive. So these plants are like humans in the sense that they have a culture, and they have their own rituals. They have their own kin. They have their own wishes, and if you will, their idiosyncrasies as well. They can be capricious, or they can be severe. They can be comforting. They can teach you. They can inspire you. They can punish you if you don't follow their instructions.

Why is this important? Because this talks to a fundamental dimension of what these substances mean for Amerindian thoughts. And of course, here I'm doing some generalizations. There are different uses. But this is quite prominent because normally, in the West, we sort of think of nature as an object and something that is not animated.

And we place human beings on a higher scale as rational beings, as beings that own culture, that own traditions, that own the ability to reflect and to make choices. And we kind of scale plants to the bottom of this ladder and consider that plants are objects, and therefore, we can dominate and use them and conquer nature.

And this is a very important difference with all these other traditions that are considering that ontologically basically humans, and plants and everything else share a common nature, share a common culture, share a common ability to have intention, to make decisions. I want to explore what does this means if we take this seriously.

So there's some authors that have talked about the idea of interspecies communication, and these are very dense topics. I'm basing a lot on Laura Dev's chapter in our book, Psychedelic Science, which was based off Psychedelic Science 2017 that MAPS hosted, and I was one of the curators of the whole conference.

And so it is this exploration of epistemological and ontological assumptions of the process of creating knowledge because scientific research is normally based on a traditional relationship where the researcher relates to some kind of external object as we were speaking before.

And as I said already, as well, plants are traditionally excluded from the ontological status of knowing or of being animated beings. What does this mean? In other words, we limit all that exists to only those things knowledgeable by humans with specific ways of knowing. But what if we tried to take this Indigenous knowledge seriously and considered what they are saying and ask the question, how plants and humans both contribute to producing botanical knowledge?

And this has a lot of other implications because if we take this knowledge seriously, and if we really consider that plants are, in fact, humans, are beings and have agency, intentionality, then we're not going to classify Indigenous thought and practice in that realm of belief or mystical or superstition or primitive, so to speak, which in the end, ends up to be a form of rationalization of excluding other forms of knowledge and considering our own forms of knowledge superior and all the implications that this has on several levels for researchers, scientists, but also, in other levels of society.

So moving with the idea of this interspecies communication, this communication, which would be possible under the influence of these sacred plants-- so if you follow certain diets and if you follow certain rules and you participate in these rituals together in the appropriate setting with the shaman, you would be opening up the ability to communicate with these plants and see their true nature and therefore engage in this kind of interspecies communication.

How would it be if we wanted to make a science like that or a clinical practice like that? I don't have the answers, and it's a bit trippy, and it's a little bit all over the place, but I ask you to-- yeah, I'm here to try to seduce all of us with some cool ideas that are not normally how we think about these things and go beyond a little bit the stereotypes of Indigenous people, that indigeneity of the wise Indigenous person in the forest, holder of all knowledge, and really invite us to engage more with this form of knowledge.

As I said, I was quoting Laura Dev. I want to read this quote. She talks about the need of this multispecies perspective. "Approaching ayahuasca research from both Indigenous perspectives and plant perspectives can provide an orientation for revealing our human-centric and scientistic assumptions that are otherwise invisible.

Through interspecies thinking that privileges Indigenous epistemologies, there is an opportunity to restore the animacy and worldmaking activities of the other-than-humans, elevate Indigenous ways of knowing these other-than-humans, and thereby disrupt hegemonic knowledges."

So this has to do with what some authors have called decolonization or a combat to epistemicide. Epistemicide is [INAUDIBLE] other epistemologies. What are the implications, and what can we learn for the field of psychedelic science, a science that wants to legitimize itself paradoxically based on those traditional ways of knowing?

I want to call here some what can we learn for the concepts of healing. And here are some generalizations, but again, I'm trying to make a point. The psychedelic field often reduces the notion of healing to the physical properties of certain substances.

From an Indigenous perspective, healing is a more comprehensive affair that involves relationships between humans and between humans and non-humans and the cosmos. So this whole idea that you can reduce the plant to one substance, to one main molecule that has one intrinsic property, and that property can heal one specific disease is very different from these traditional claims.

And then the question is, can we translate this? Or what can we do with this? And there are simple answers for this question. As I said, from the native point of view, this distinction between the molecules and the plant teachers doesn't make a lot of sense.

And it's not all the same. We can't reduce everything to the property because these plants, they have spirits. They are alive. They have a personality. And you learn to engage with them. And it's this set of relationships that brings healing, when you can relate to yourself, but also to others and to the cosmo, to the world beyond us, to the invisible world, to the world of the ancestors, to the primordial times, that is when you have healing because disease is often an imbalance on all of those spheres.

So we can't just reproduce, appropriate, or imitate a set of techniques that comes from Indigenous peoples. We should be able to both decolonize healing and also reconcile our relationship to native people. And here, I want to make a point that is important, which is the relationship to the land. These plants just don't appear out of the blue anywhere. They have a relationship to the territory and to the people that are traditional to that territory.

So I want to bring back that photo that I put in the beginning of the conversation. Let's remember that the Native American church emerged out of a need to respond to colonialism and political pressures to break cultural practices and sever connections to the land.

Even in forced relocation, the Native American church was pan indigenous in a deliberate effort to acknowledge the way that people were being moved off of their land and away from kinship ties and cultural rights. Peyote and others therefore also offers a land-based healing that cannot simply be replicated by imparting the substance just as Westerners cannot simply impart these traditions into a Western model.

And now I'm going to take a little bit further, and I want to challenge a bit this idea of set and setting. And again, I want to ask you to be open to that. And as an anthropologist, it cringes me to see the use, with all my respect, that some medical colleagues and others in this field make of this concept.

The idea of set and setting in clinical trials is represented often by scientists as a fictitious equivalent to Indigenous ways of using these substances. And Indigenous knowledge is frequently misrepresented in the biomedical research. And this is something that I want to make a strong point of.

When you talk about set and setting, first you have to understand that this is a theoretical construct. These categories were created by us, and they are, to start off with, limited because one thing intersects with another. But even following-- some authors have challenged those distinctions.

Even if you follow these distinctions and if you want to work with these categories, it's important to understand that people seem to treat the idea of setting as if it were some kind of decoration, like if you worked in a movie theater, and you're trying to put-- let's put some perfume. Let's put these clothes on. Let's put this picture on the wall. Let's create a nice music. Let's try to make a beautiful author.

I want to prepare a set and setting, and people have not really understood that this is not the concept of setting. Setting has to do with these much larger concepts, which is the cultural container, the social and cultural and historical conditions and frameworks on where the substances are used.

So I think this is very important to do because I feel that it's this need to use Indigenous people to legitimize scientific research while at the same time not taking into account Indigenous beliefs and trying to reduce things that are much more complex and sophisticated and have a whole history and set of relationships to categories that we invented and our projections of our own values and systems.

And so I think that there is this great [INAUDIBLE] which starts with this conceptual mistake around the notions of set and setting. And this continuity with this knowledge that often doesn't take into account the people and the real Indigenous people that exist in the world today and that have things to say to us.

So I want to talk about integration, and here, I'm a little bit afraid that everybody will hate me. Again, I'm not against integration, and I think it's all good. I just want to try to bring some new ideas. Can we try to think of this on different lenses with an anthropologist queer from Brazil? I invite you to think about this topic in a different way.

I feel that integration has become this complete loose concept that includes everything. It's a kind of mishmash that I often don't find it useful any longer. It's also really not clear who can do integration for whom and on what terms and what are the proper training you have to do this integration that seems to be so important.

So again, the psychedelic fields seem to have fabricated a common sense notion that integration naturally exists amongst Indigenous people. And I want us to look at this because this, again, is a way of not looking at Indigenous people and what they are saying and they are doing and trying to appropriate this for our own benefit without even giving an effort to understanding different epistemologies and ontologies.

So this idea that integration is really necessary, and again, in a super commodified, postmodern, fragmented world, that everything is put into a price, and everything moves fast, and our culture of privilege and video clip, you have all of a sudden the creation of a whole new set of experts.

I see a lot of people naming themselves a psychedelic coach, psychedelic integration expert like their main identity. And this also is heavily marketed with a new set of obligations and products in an increasingly competitive landscape, which is this recent arrival of millions of dollars into the field of psychedelic science and psychedelic therapies and the blossoming of this new industry with a lot of people that come from the outside, have never tried psychedelics, and don't understand the particularities of psychedelics or any of the history of psychedelics.

I feel that often this idea of integration goes with an excess of verbalization, rationalization, and attempts to control things. Again, I'm not saying that integration is wrong or bad or people shouldn't do integration. I plenty understand that there is a big need for conversations, and people are really eager to sit in circles and talk about their experiences.

But I want to be able to say things more openly and just invite questions, even if they are paradoxical and hard, and we don't have clear answers. I think it's important to ask this. And again, as me as a Brazilian who has a larger experience in the field of ayahuasca and have dedicated most of my career to studying ayahuasca and also have lived and worked eight years in Mexico and done field work around peyote and have also sat in to this in more contemporary, urban, cosmopolitan circles, I have felt often overwhelmed with these integrations that I was forced to participate in some of this context.

And that's why I'm inviting us to think of other means and other forms, for example, silence or music or art or just the enchantment, the invisible. That is not verbal. Let's not forget that all of this is mediated by language, and it's a representation of the experience. It's not the experience, per se. It's also something that people often forget.

So whereas integration can be important for Westerners, we should try to look at what Indigenous people do and learn new ways of knowing and healing. And maybe, this could help us revisit some of our own categories and our paradigms because this is what I think is fascinating about psychedelics. They really help to break a lot of paradigms that we were socialized with, our very notions of self, of time, of space, of the invisible, of the future, of the past.

And here I'm going to try to advance this dialogue between ceremony and psychedelic assisted therapy. So there is a fundamental epistemological difference between ayahuasca shamanism and psychedelic therapy as no shaman or guide would ever be considered legitimate without consuming the substance himself.

This division show how, from certain perspectives, therapists did not need to consume the substances because the substances are able to do something, and they are not a plant spirit to which we dialogue with. So there is this question. Should the psychedelic therapist try the substances and consume it? I think yes.

And I have co-led a group of therapists to drink ayahuasca in the Amazon, very intense experience having a lot of therapists processing their experience. And I think one of the main points that that group came out with was that how can psychedelics help the therapists in their clinical practice.

I think, first of all, it helps people learn about themselves better, know themselves better, and if they know themselves better, they are better people, and they are more able to be better therapists. And so I think cultivating this personal practice is important, although I'm not here to be a messianic prophet that everybody should consume psychedelics because we also know that psychedelics is not for everybody, and there are some mental health conditions and other contexts that it's particularly not inviting.

But I think that even historically, Western therapists in psychoanalytical tradition, if you look at it, they could not offer therapeutic advice without having first experienced this as a patient or client. So I think one of the other takeouts that I'm trying to make a point here is there's ways that we can try to incorporate the sacred into clinical practice. And one of the things that is important or possible that we learned with traditional groups is the importance of group settings, so perhaps group therapy.

And I want to also just do a special shout out for the importance to cultivate humor because in our attempt to be so solemn and so deep, we frequently forget that humor is highly healing and central in many Native American traditions. I personally like to do a lot of jokes and enjoy a lot of random commentary about things. And I have said the shaman often talks by tales and by jokes, and it's important that we also cultivate this modality of knowing.

And so coming back and repeating a bit some of the points that I mentioned already, healing should not be centered in the individual. Healing is relational. Healing has to do with the group, not just with us, but with what's beyond us as well. And also, these substances, they can help us cultivate our own ancestry and look to our own roots.

So sometimes people-- as a Brazilian, I also think it's funny because there's so much fetishism by the global North on our culture and our traditions, and people like to idolize a lot Indigenous people. But it seems to be something universal or cross-cultural that these plants can help one investigate one's own ancestry and one's own roots and identity and sometimes recover some aspects of those identity that have been lost or is marginalized, such as your gender or your race. So again, paying attention to the territory.

And also, it's an invitation for everybody to engage in activism. I personally think that doing activism is one of the most liberating things and brings a lot of existential comfort, and it's a way to bridge this gap, this colonial legacy and these paradoxes of colonization and epistemicides that we promote and that we are all [INAUDIBLE] even when we're thinking we're not. And so again, it's this invitation to look at these things more from a global and holistic perspective where everything is interconnected.

And here, I want to make just a few slides about what are Indigenous people telling us. So here, again, another picture from Clancy. A big shout out, she's one of the most solid allies and has been a lot behind my work for over 10 years that work together. And we are co-editors of eight books, and she's also an artist. This is another painting of hers. And the question that I want to pose here is, Indigenous people are speaking, are we listening?

And here, we published a series of these articles in our sight, chucrana.net. This is by the UMIYAC, I am sorry, and this was an important declaration that almost got no visibility at all. This is a document where the elders speak, and they are speaking to young Indigenous people, and they are also speaking to those young Indigenous people that are not really prepared or pretend to be tied to us and go around offering ceremonies for foreign individuals. They critique non-Indigenous people who appropriate and abuse spiritual practice.

And they have a strong statement. They are saying, no one outside the Indigenous communities can cultivate, sell Yagé, or officiate ceremonies. Yagé is the name of ayahuasca in these Colombian native traditions. And they say that non-Indigenous people that are using Yagé should have endorsement from Indigenous communities. They are criticizing the commercialization of ayahuasca or Yagé and the traditions, denouncing cultural appropriation, critiquing this often mix of traditions and plants, and also, alerting to health risks.

In Brazil, there has been a strong movement of the creation of Indigenous conferences by Indigenous people and for Indigenous people only. And this is very interesting. Their first article came out as a critique of the World Ayahuasca Conference in 2016 in Brazil where a lot of Indigenous people were invited and didn't feel that they were properly treated and incorporated by conference organizers and launched a strong critique of the conference in the closing days of the conference, and after that, started to organize their own conferences, which is also interesting because in one way or another, the World Ayahuasca Conference ended up helping benefit this pan tribal and pan Indigenous alliance that is happening in Brazil.

And what is happening in Brazil now is a strong politicization of the Indigenous movements where also the Indigenous people are talking about the importance of gathering for Indigenous people only. And they are talking about the needs to promote internal self-regulating relative to relationship to non-Indigenous people. And they're also saying, hey, there is no need for scientific proof that these practices and traditions and our sacred plants, they really work. That's very interesting. We're not interested. We don't need really that.

They're also making a critique of commercialization of Indigenous medicines and rituals. But they're also promoting proactive partnerships, such as projects or festivals, the famous Indigenous festivals that they hold where the whole tribe hosts a bunch of foreigners and outsiders, and other services. So they're also saying we need help from outsiders.

It's important to understand the context of these Indigenous people where they are completely abandoned by Latin American governments, such as Bulsonaro who is actively engaged in the genocide of Indigenous people. And a lot of times, Indigenous people can't count on foreign alliances and money to be able to thrive and survive.

So it's not also just this complete rejection. It's a call for partnerships, partnerships that are co-collaborative, horizontal, decolonial. It's a partnership where I ask the other, how can I serve you? How can I be of support, and not just bring the other to my own activity.

In the US and Mexico, same thing has been happening with Indigenous people. We also published this Native American statement regarding the decriminalization of peyote. Some of you might know that there has been a huge controversy, very intense between Decriminalize Nature Group in Oakland and the Native American movement in the United States where there has been a real lack of dialogue.

And Native Americans haven't felt really heard and have issued this statement basically calling for the need to include native voices in the table, a space for native voices and a statement against the decriminalization of peyote and a call for Native Americans to be in charge or leaders in conversations regarding the protection of peyote and special rights that Native Americans have.

So this has been a clash between the idea of cognitive liberty or the right of sovereignty through my own body and mind and privacy and autonomy versus Indigenous rights. And peyote is a real complex mix because it really involves the health laws, the drug laws, and also, conservation laws.

Recently, the Wixárika people have also come out with a similar statement. They're not so much emphasizing against decriminalization but more against the misrepresentation. It's this paradox that I want to count on Indigenous people to say, these substances have been used forever. They're used by thousands for millennia to heal. But when it comes to dealing with the concrete Indigenous people that exist here today and now, we often are failing.

So I invite all of you to read [AUDIO OUT] just open to sharing more. We have the whole session about reciprocity, Native Americans, cultural appropriation, and conservation. We have our Counsel for the Protection of Sacred Plants and a lot of published materials that we can share with those that are interested.

So the question is, what can we do? How can we as psychedelic folks and activists engage? And how can we be better allies? And it's a bit funny that we have a lot of allies to Indigenous people that have actually never worked with Indigenous people, have no background or publications or any kind of field work.

So how can we show up, and how can we be of service? And how can we work on these categories that I've been advocating here for cultural humility, for collaboration as academic researchers, as non-profits, as individual people that use psychedelics?

I'm going to outline here some of the initiatives that here is a little bit more pointing towards some of the work that we have been doing in Chacruna. We held this conference, Plantas Sagradas en las Américas. It was chosen to be in Lake Chapala, a cardinal point in the Washirika cosmology.

And we had 25 Indigenous people, and a lot of them spoke a native language or did music and poems and talks. And we really put them as keynote speakers and tried to give them special space and with more visibility. All the people we invited were invited through people that do have connections in the field. So we're really avoiding tokenization and just get an Indigenous face out there so I have some representation.

And this was a really powerful conference. And it was all in Spanish. And it was free. And it was a statement that we were trying to do about what we're seeing as some of the new experts and the new people benefiting from all of this for the self-appointed conference organizers or other so-called experts with little connections to the fields. And it was a really rewarding experience, and we're going to try to repeat this online. I don't think it's the same, but anyway.

I want to share. We published these guidelines, How to Include Indigenous People in Psychedelic Conferences. And so a lot of people look me up. Hey, I'm looking for an Indigenous person to sit on my council and to give some representation.

And I want to invite people to think, imagine if you're an Indigenous person in the Amazon, and you have all your problems, and it's pandemic, and et cetera. And then you find this person from the US that doesn't speak your language. Hey, do you want to sit on my council? It's like, no. I need money to go take my boat and take my son to the dentist.

And so it's really about this basic anthropological exercise, which is trying to see with the lenses of the others. How does this feel from a Native perspective? And what is there for natives in those enterprises? And what is there for them? And just really, we have to talk about very basic things, like when you host native people, put them in the same accommodations that you're hosting your non-native speakers.

It was funny because I was inviting the UMIYAC to give feedback to these Indigenous guidelines, and they were saying, Bia, do we really need to say things like that? And I said, yeah, unfortunately, because the experience has been that these things don't happen. And so a lot of people want to talk about Indigenous people without including Indigenous people.

And you can also change Indigenous for Black. It works as well. Frequently, we-- I want to organize a panel into a [INAUDIBLE] about diversity and African-American experiences, but it's a bunch of white therapists, and there is one person of color in the panel. And then, there's also the importance of compensating your speakers even if modestly, especially when they are speakers of color.

We have also been producing a lot of articles that try to talk about all of this. I'm just naming some. "Sacred Reciprocity" by my dear friend Celina de Leon, and she is Bryan Anderson's wife, and by the way, they just had a baby, and long life to them and their family. And the new come into this pandemic crazy world, but still sweet and full of opportunities and work, good work to do.

We've also published this one, "What Do Psychedelic Medicine Companies Owe to the Psychedelic Community." There's a new trend right now that is psychedelic businesses that want to give back to Indigenous people. So psychedelic businesses that are trying to create products based out of ayahuasca and peyote, and how can they do that, and is this fair? And it's on the making.

The cool thing about this field is everything is so new, and we're seeing everything develop in front of our eyes now. And we're a witness and creators of this story. So also, I know this is a lecture that has students and many people that are thinking of going into the field of psychedelics as their career. I really want to encourage you to do so. We really need some good people. We really need some people with a lot of energy, and there's a lot of good work to do.

I'm naming just a few articles, but there is a lot of really good materials. I also want to give a shout out to Joe Mays, and he is one of our dear team members. And he wrote this piece, "Supporting Indigenous Autonomy Means Participating in a Story of Relationship."

What does that means? It means that it's not just about money. It's about creating this relationship. It's about slowing down. It's about creating trust. It's about engaging in a personal relationship and also, being open and being vulnerable to this relationship. And I can assure that is incredibly rewarding.

And if you honor minorities and if you give them voice and if you put your platform in their service, they are going to respect you and collaborate. I can attest to that. Also, sometimes they don't want to collaborate, and then you have to accept that. And not all Indigenous people use psychedelics. We also should not fetishize Indigenous people for the psychedelic uses.

And remember that a lot of Indigenous people don't use psychedelics, and a lot of Indigenous people don't want to have anything to do with your conference or with your publication or with your academic thesis, with your internship, with your businesses. And we must be able to respect that as well.

Here are some of the other articles that we've been publishing. I really recommend "The Commodification of Ayahuasca." It's a paper by us where we're trying to create a culture where people will drink ayahuasca and think about the context where they're drinking.

Check out the sites. Do they tokenize Indigenous people there? Are the names of all the white facilitators and the owners given, and when it comes to the Indigenous person, he has no name? Do you know what is his name? Do you know what is his ethnicity? Is it clear where ayahuasca is sourced from? Is it clear if these Indigenous people have some kind of agency and saying in your institution because tokenization is about representation having these different voices, but you got to give power to those voices.

So it's about diversifying your retreats, your non-profits, and making sure that people of color are there in positions of power and with the same. And if you create a social justice group inside your organization-- I know of a super nice nonprofit that has this social justice hub, but they have like a gatekeeping group that doesn't allow other people to join the social justice group where you're going to advance this conversation.

So there's so many paradoxes. And we're also just really trying to bring Indigenous voices into the mix. And we have published a lot of different articles. This is one by our friend, Inti Garcia, and Sarai is an anthropologist based in Mexico, "Mazatec Perspectives on the Globalization of Psilocybin Mushrooms."

And Diana Negrin, who's also part of the Washirika Research Center and is going to launch a Washirika healing visionary art series with us too, has been writing a lot about the colonial shadows of the psychedelic renaissance and the need to include the voices of Indigenous people among many other anthropologists that have written about these topics like [INAUDIBLE] and [INAUDIBLE] and [INAUDIBLE] and many other colleagues that I very much cherish and respect. In Chacruna, we are really engaged in group work and teamwork and in big conferences and production of big books with a lot of different voices.

And so I want to just conclude by presenting the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas. This is our new baby that we're petting and that we share and appreciate. It's our project that we are so carefully and tenderly creating.

And we're trying to create a support to Indigenous-centered, community-driven projects that attend to self-determined needs that speak to Indigenous autonomy, so projects from environmental health to land-tenure, reforestation, and cultural conservation, including educational, economic, and institutional support.

What is this resource? We have been doing since more or less August last year a big map based on our links in the community, our field work, our anthropology ties and a person that is working especially on this trying to map all grassroots organizations that exist all throughout the Americas-- so initiatives that are led by Indigenous people by Indigenous people for Indigenous people.

And we're going to be publishing this resource soon in our website. And we're going to encourage two things. All individual psychedelic lovers and enthusiasts and people that have found so much healing, blessings, and magic in our beloved sacred plants can go to this page and pick one of these initiatives and donate directly.

We're also going to have a private meeting with some businesses with some of these new big players that are emerging on the fields and trying to educate them about some values of the psychedelic community and offer them a chance to reciprocate.

And we're going to collect these donations, and we are only charging a fee of 5% because we don't see this as a way of Chacruna making a living, but rather really an opportunity that we have due to our special ties from the global North and the global South and anthropology and biomedical and English speaking, non-English speaking realities that we are in a privileged position to offer this opportunity. And if you want to learn more about it, I invite you to write to us.

I also want to invite everybody to come to our conference Sacred Plants in the Americas, total kickass initiative that we're doing. We're going to have three simultaneous tracts, over 70 speakers, 12 panels, 39 individual talks, a lot of Indigenous people from all over the Americas, and about six panels and talks focus on the topics of decolonization, reciprocity, decolonizing wealth, giving back to Indigenous people, creating more mindful business models as the psychedelic renaissance advances and blossoms or blooms.

If you enjoyed my lecture, you can follow me on Instagram or Twitter @LabateBia, or you can also volunteer to Chacruna. You can register to our newsletter. Also, as we say in Portuguese, don't be afraid to donate. Do you have a snake in your pocket? I don't know if this translates. It means don't be afraid to put your hands on your pockets. If you like the work of the Chacruna Institute and our vibe resonates with you, please donate now.

You can also become a Chacruna member and join our Patreon membership. I want to invite people to also follow us in our newsletter. Especially, Brystal, Carina, Josh, Grace, and many others that have supported these conversations.

And you can put your phones there, and with this, you can be directed to our site. And yeah, thank you for your time, and thanks again for everybody for listening to me and for the invitation. I am concluding in this virtual space where I can't see anybody, but I hope you're all there.

CHARLES STANG: Well, I'm here. Bia, that was wonderful. Thank you. Wow, lots of questions. And we can't get to all of them, but let me say at the outset that we will share with Bia all of the questions and comments, and unless your comment was submitted anonymously, Bia will also have your email address. So if she feels moved to write you an answer, she will have the means to do so. But if you submit your question or comment anonymously, she cannot.

OK, we have so many questions. So I'm going to start near the top. This is a question from Suraj Sharma. What are your thoughts on the chemical synthesis of the psychoactive compounds within these plants and their consumption being disconnected from the original plant setting they're normally consumed in? So the synthesis of these substances, what are your views on that?

BIA LABATE: Well, I don't think it's useful for us to say I'm against it or that I don't like it. I think that this is a phenomenon that is happening, and it's predominant. And so what we're trying to do here is to think of ways that we can make mindful uses and create harm reduction around this phenomena of synthesization of plant medicines.

Also, there's a lot of angles. Some people can argue that it's better to use synthetics than the plants and that attacking plants will damage their natural environments, and so it's better that we use synthetic plants. And other people will say that this kill the spirit of the plant, and it's not the same.

The important is to keep the questions alive. And what bugs me is, for example, people say, oh, [INAUDIBLE] took mushrooms to Maria Sabina and the synthetized psilocybin, and Maria Sabina said, it's good, it has spirit. And so I watched a lecture from [INAUDIBLE] once that he's saying, well, imagine if somebody brings a cake to an old lady in her house, a humble lady. She's going to say, yeah, good, thank you, I appreciate it.

You can't just say that Maria Sabina said it's good, and therefore, she gave the blessing, and therefore, all our existential issues regarding the deep epistemological issues are done and are dealt with. I think what I've tried to call the attention here is that we have to be doing some critical thinking about all of this.

CHARLES STANG: OK, thank you, Bia. Here's another one. This is from Rachel Sotos. I'm curious if there's something we might recognize as quote, unquote, "critical" in Indigenous psychedelic experiences? By which she means, an experience of transcendence that is or can be specifically posed against different forms of knowing political standpoints within an Indigenous culture itself. So a kind of imminent critique within Indigenous culture enabled-- these are my words, this last-- an imminent critique enabled by psychedelics within an Indigenous culture itself.

BIA LABATE: I don't know if I understand the English of all this complex question. I'll give my answer the way I want to give. That's what politicians do, right? They just say what they want to do. They use the questions to say what they want to say. Well, what I think is that Indigenous people often use psychedelics.

For us, we talk about psychedelics being counterculture and something alternative or progressive or anti-establishment, anti-status quo. Traditionally, psychedelics have been used at the core of culture, as a means of transmitting culture, as a means of socialization, celebration, of creating art. And more importantly, frequently, psychedelics are tied to the very stories of origin of humankind and men and how we came about to be what we are.

CHARLES STANG: What about means of critique?

BIA LABATE: It's not exactly a critique. It's a critique in the sense that society is always critiqued, and there's always different angles to everything. But what I'm trying to say is that it's more in terms of transmitting culture and affirming culture and passing on culture.

But also, these groups are not static. So they will have different views and different understandings, and different generations also have different approaches. A lot of the declarations I read, for example, contrast the elders' views with native views. And there is space for different perspectives on different sides.

It's very challenging to be what is to be an Indigenous person in the 21st century. And so there's a lot of different understandings, and psychedelics have been a way, a place where these conversations happen, especially around what it is to be Indigenous.

And for example, there is one of the articles that we published in our book with Oxford University Press, that Ayahuasca Shamanism in the Amazon and Beyond, talking about mixed scenarios where Indigenous people sit in the outskirts of the city of [INAUDIBLE] to drink ayahuasca together with members of non-profits and other displaced Indigenous people from other communities, and through these ceremonies, learn how to continue to be Indigenous. And so in that, there is critique as well.

CHARLES STANG: Let me shift gears. You said you weren't going to speak about the varieties of Indigenous use, but I want to-- I'm paraphrasing the question here. So if in Indigenous use, you have examples of group use of psychedelics, at the same time, you have individual use.

And in individual use, you also have the possibility of, say, a representative, like a shaman, uses psychedelics for the benefit of his or her group, and then the possibility that also individuals, people in the community, not the shaman, may be using psychedelics for their own purposes. How do those three models, and there may be many more, I don't tend to know, but how do those three models-- what are the implications of those models for something like psychedelic assisted therapy?

BIA LABATE: The models being which ones?

CHARLES STANG: Well, roughly group use, like a number of people using psychedelics together. Another being individual use, but for instance, for your own purposes. And then, a third might be individual with a kind of shaman who is using it for the purposes of healing or knowledge or but turned toward the client or his or her own community.

I guess what I'm trying to get at and this question is trying to get at is so much of the psychedelic assisted therapy is still on this individual model of a therapist and a client, one on one. How is that in some tension with the variety of uses of psychedelics in Indigenous contexts?

BIA LABATE: Yeah. What I will say is that I feel that this one on one is not exactly-- in Indigenous setting, the experience is much more collective. And also, even if you're just using alone in an Indigenous setting, it doesn't mean that much because we have to understand that these groups have different ideas from self and from individuality, and that the categories in which they operate are entirely different.

For example, a lot of these societies don't have a government. What governs you is kinship and structural relationships. So who you are in the chain of relationships of that society determines a lot about your expectations or obligations. So it depends if you're an anthropologist who has studied a lot kinship systems of Indigenous people, which are very, very complex and sophisticated.

Our kinship system is rather dull, and we see uncle, uncle, father, mother, cousin. indigenous people sometimes will recognize up to 400 levels of kinship, and it's different, for example, if it's the brother of your mother. Your mother has a brother or your [AUDIO OUT] from an indigenous perspective.

So this again, trying to say, oh, he's alone or not alone. I think it doesn't translate completely well. You can say it's an individual use, but the idea of individual in this society is entirely different, and this is what I'm trying to say here. And also, people confuse a lot. For example-- anyway, there's a lot of different examples.

People tend also to think that all the uses are sacramental and are shamanic, and not all users are sacramental or shamanic. For example, tobacco can be used kind of recreationally so to speak, as a socialization among a circle of men in the end of the day will sit and smoke tobacco together.

But that's not exactly the same recreational use that it is for us if you want to translate the categories because it's still embedded in these other views because the world of shamanism is a world of relationships. It's a world of predation, and it's a world where you have constantly to be answering to spirits and to the spirits of the plants and following certain rules.

So you say, if you're menstruating, you can't sit. Oh, it's because the woman is more vulnerable. No, it's because there's a economy of relationships between men and the spiritual world that is at stake. It doesn't translate into breaking this into little rules. Then we project our own categories into that. So there are some levels of [INAUDIBLE] answerability. And there are challenges in translation.

CHARLES STANG: All right, this is from Helen [INAUDIBLE]. Forgive me if I've mispronounced your name. Bia, with regard to your views on psychedelic assisted therapy, that the therapist should be experienced with psychedelics-- that's this question asked-- do you mean that the therapist should, in this case, drink together with the patient during the session or that the therapist should just have experienced it at some point in his or her life?

BIA LABATE: Very good question, and I feared somebody would ask that. So I know Helen. Hi, Helen. And I think for sure, you should experience it. I personally wouldn't trust somebody that hasn't had any experience. Although, having experience doesn't make you a great therapist either. There's a lot of people with a lot of experience that don't get it. And I think for sure having at least once in a lifetime is important. And I think cultivating some kind of self-knowledge practice is also important.

In regards to consuming during the session, I don't think that's possible in our current FDA regulatory schemes. And I'm also not sure if this therapist would be qualified to do so. So it's a bit delicate. I don't think we can go around saying now everybody has to go drink ayahuasca or eat peyote or take MDMA while they're doing the experience.

But I'm sure we have a lot to learn with the underground. And I think that this is something that also needs a lot of research and has been very much under appreciated and under researched, which is understanding the practices of the underground therapists who have a lot of experience and frequently have sat in a lot of circles and have done a lot of soul searching. And so I think we have to have more of these conversations and ask this therapist what do they think. It's a bit hard because it's hard to come out as one of those.

CHARLES STANG: I have to actually interpret a number of these questions, and specifically, I'm trying to interpret a rather critical thread that appears anonymously. I think this is the same anonymous comment and question. One piece of it is, are you being presumptuous in assuming that Indigenous people wish to be honored?

And closely connected to that is, why have you not named the Indigenous peoples and spoken in generalities about Indigenous peoples? If you wish to honor them, should you be naming them? I think I've reproduced those questions faithfully.

BIA LABATE: Yeah, it's a very good question. But I plenty agree that you should name Indigenous people when you're talking about Indigenous people. However, the objective here was to give a general lecture about the phenomenon in general. And there's dozens of Indigenous people that one could name or not.

And so we've also published a few articles about the needs to name territory and Indigenous people by their own lands. I did mention a few. I mentioned the Washirika and Belinda, [INAUDIBLE]. And there's different ethnicities in the Native American church. I definitely think that it's important to name those.

And also, the continent, a lot of people have chosen to name the name of Indigenous lands, for example, by the Indigenous names, and so both the ethnicity and the land by the original names and not by the nicknames given by the colonial settlers. So also, we published an article about calling America Ayala. There is a big movement of decolonization about that.

And I think in terms of being presumptuous, it's a good provocation, and I take it. Yes, maybe some Indigenous people don't care, don't want to be honored and don't really care for the ideas that I'm expressing here. However, I'm not speaking just out of my own wish. I do have my own relationships and collaborators, and I like to keep accountable to them.

And I don't know who is the person that asked that, but I like to think that we should be keeping accountable to the people that call us allies more than to the people that are just from the psychedelic field. So if some of the native collaborators that have interacted with me in the last 25 years feel that this message is mistaken, I wouldn't take it. I don't think so. I feel a lot of Indigenous people are open to this dialogue and need it and are claiming for it.

But yes, I think there is a good point in that we can't take for granted, and I tried to make that point saying that sometimes Indigenous people don't want to participate and don't want to get involved, and you should leave them alone. And while organizing our conference, Sacred Plants in the Americas, believe me, we get a lot of that.

And we also get a lot of people that participated in other psychedelic conferences not by Chacruna and then don't want to participate in any other psychedelic conference. Perhaps one of the main Mazatec speakers that is circulating around recently, he spoke first in Sacred Plants in the Americas in Mexico in 2018. And now I spoke to him. He has a real burn out because he has became the Mazatec that everybody's inviting to go everywhere, and he doesn't want to go anymore. So yeah, those are very good questions.

CHARLES STANG: There's a whole host of questions that are about suggestions for further reading, I feel as if those questions would be best answered in mass by saying spend some time on the Chacruna website where you can find a number of these articles that you've mentioned. But is there any particular book that you would recommend in particular people start with?

BIA LABATE: Well, if you like peyote, I really recommend our book on peyote tradition, conservation, and politics. Ayahuasca, we have, I think, four or five books on the globalization and internationalization. There's Ayahuasca Shamanism in the Amazon and Beyond, but we also have The Internalization of Ayahuasca.

And we have two books with Rutledge, The World Ayahuasca Diaspora. There is part one and part two. We have a different book on Ayahuasca healing. We're coming out a new book right now. We have a few books in Portuguese about sacred plants.

And I really suggest you visit the sessions of inclusion and diversity on our website in our "Chacruna Chronicles." And also, the session of policy has a few of those articles. We can also provide a series of recommendations of articles talking about some of the main ideas discussed here. But some of the things that I said, I just created for this lecture as well. They are things that I want to further develop and haven't published about.

CHARLES STANG: Here's a question from a good friend of the CSWR, Joseph Prabo. Hello, Joseph. Joseph asks, it takes a whole series of revolutions to move from a commercial, colonial, and imperialist culture to a culture of relationship and reciprocity.

Speaking politically and pragmatically, what are the best practices that might help in this cultural and epistemological dialogue? It's an enormous question. You must know Joseph. He's in California at CIAS, I think. Well, anyway, carry on.

BIA LABATE: Yeah. There's so many angles. I think the main question we always have to ask is when you are doing anything that involves Indigenous people is to try to see what is there for Indigenous people in this initiative is to try to do this exercise, and also, to talk to people, to talk to locals, ask questions.

And if you're really, truly interested in learning about other cultures and other societies, you have to learn their language. Really, learning a language is a basic thing. Just speaking one language is very limitating to a certain world view.

I might be very biased, but I say reading anthropology is very important as well. I would also like to invite people to visit our website. And I think it's always about trying to make-- like my friend, Monica Williams, was saying. We had a conflict in a conference that somebody said the n-word, and she was commenting to me like, do you think that if it was a white person, nobody would come out and say anything? Because if somebody criticized your cousin or your friend, you step up and you say, no, I don't accept that. That's wrong. Why? Because they are your friends.

So I think it starts by making friendships. If you make friendships with Black, Indigenous, and people of color, and that's the beginning of everything. I felt very blessed as I moved to California and made some really good new friendships over here with some African-American kickass researchers and doctors and activists. And we were influenced by their work and friendship. So creating co-authorships and also engaging in concrete actions because actions are better than statements.

And if you're creating some kind of joint initiative academic research, ask locals what do you feel is useful, how can we help you? What kind of research would be important for you? And if you're a teacher, try to diversify your references. Try to put other authors as references and not just anthropologists or white people, and try to engage in South dialogues, and engage in activism. There's so many angles. I hope I said--

CHARLES STANG: I know you've been going for almost an hour and a half straight, but I want to ask you two questions, and then we will bless you and send you on your way to conclude this event. Rebecca Stromberg has made a number of comments and questions, and I'm going to ask her latest, which is this.

The globalization of plant medicines is happening. It's already happening. Do the plants want to globalize? I know you can't speak for all plants, but I'm curious if you can speak about perspectives on the will and agency of the plants who are being globalized. What do plants think about their globalization?

BIA LABATE: I don't know what they think. I don't feel I have a press pass from the plants. I remember once in this ayahuasca retreat with this guy that has a TV show. And he drank ayahuasca, and on the next day, he had this scene showing his big muscles and small shorts and looking to the horizons. And then the filmmaker filmed him. And he said, "Ayahuasca told me--" I'm like, wow, you drank ayahuasca once, and now you got a press pass to say what ayahuasca is telling. And that's going to be on the BBC.

So it's complicated to speak on behalf of the plants. I don't feel I have that pass. I feel a lot of people have used this argument to say the plants are coming out of the forest, and they want to teach us. This has been used to legitimize the globalization of ayahuasca. Or ayahuasca came out of the forest, and now it's here to heal us and heal the Amazon. On the other hand, maybe the plants are trying to do something, and we don't know.

And also, one of the authors that I like a lot in my readings is Sylvia Miestradeni, and we published an article about this kind of thing. She's called "The Entangled Ayahuasca." How can we create this research and understandings that take the perspectives of ayahuasca into account? And I also mentioned, Laura Dev here about interspecies communications. So not everything we can explain, and there's a lot of things that are just hard to know. And a lot of the explanations, you can contest anyways. So that's my answer.

CHARLES STANG: All right, one last question. Manvir Singh in December in Vice wrote an article entitled "Psychedelics Weren't as Common in Ancient Cultures as We Think" calling into question the antiquity of psychedelics specifically, I believe, in the Americas. I'm wondering what you think of the debate around the antiquity of psychedelic use in the Americas and what matters in that debate, whether and how it matters how many hundreds of years Indigenous peoples in the Americas have been using psychedelics. What's at stake in that?

BIA LABATE: That's a very good point, and [INAUDIBLE], he also wrote an article about this for our book, "Internationalization of Ayahuasca with [INAUDIBLE]" where he's trying to say that ayahuasca is much more recent than we probably think it is. And then, he has been contested, and there's a whole dispute. Also [INAUDIBLE] wrote an article for Chacruna site saying the exact same thing, that psychedelics are much more recent sometimes than we think.

So I think that what's at stake here is why do we need to have this idea that things have been existing since the beginning of times illegitimate. Why do we have that need? And I think that speaks a lot to voids in one's own Western society about these things, that you have to find this kind of tradition and originality and idea that this exists since ever, and therefore, it's legitimate.

And also this attempt to always look at the culture of the other and try to legitimize our own culture based on that other. So why do we need to say that because Indigenous people used it since ever, this is legitimate, and therefore, I have the right? And I think we should encourage to find our own legitimacy in our own terms. And this can be legitimate. It can be new because it's a new ritual, but it's also legitimate. It's a new practice, but it also helps people and serves the purpose.

But I wanted to ask you something, Charlie.

CHARLES STANG: OK, great.

BIA LABATE: What kind of thing were you hoping that your audience benefit by this sort of approach in the context of your Center for the Study of World Religions? What is it that you feel that is missing in terms of recognizing Indigenous religiosities or spirituality?

CHARLES STANG: So specifically tonight, your lecture, what was I hoping? Well, this series started with Roland Griffiths' lecture. So we sort of spotlighted the research at Johns Hopkins University and these amazing therapeutic outcomes they've had. I asked Roland quite a bit on their appeal to the category of mysticism.

And then we heard in a second event from two women who had participated in the Johns Hopkins trials and the New York University trials respectively. And we tried to put their testimony in the context of the history of religion. So we had Jeff Kripal from Rice help us with that.

I think what your lecture has highlighted is that there's-- and I should say, I'm new to the conversation around psychedelics-- but one thing I have noticed is that the predominant conversation, the so-called second wave of psychedelic research or the so-called psychedelic renaissance, is really taking its lead from the scientists.

And among the people who are not prominent in that narrative are Indigenous people. And even if it's not Indigenous voices themselves, the Indigenous traditions are not particularly prominent in that even as enthusiasm for ayahuasca continues to spike popularly.

So my hope in inviting you was to help us to begin to navigate that territory for those of us who are fairly new to the conversation. I'm including myself there. And I recognize that there is no one lecture that can even remotely begin to unpack all the sides of this topic.

So I know you were debating between what angle of approach to take. And I think you took a really helpful angle from the perspective of the series we've curated here because the kinds of interventions you have made, some of which have made participants uncomfortable, challenged assumptions they've had-- and you'll see that in the comments when we share those with you. There's also, I should say, a choir of appreciation for your lecture.

But I think that your interventions have been extremely timely in what we've been curating here. We needed someone to point out some of these blind spots but also just raise questions. I feel like that's been the most significant contribution of your piece is to just raise really lively questions.

And I also have to say I appreciate among the other things your appeal to humor, not only your own humor, but just that, hey, psychedelics work with humor, and maybe we just need a little bit of-- we need a little periodic levity because it can get so-- it can be belabored by a kind of gravitas that, I don't know, I find somewhat alienating.

BIA LABATE: That's also Native American, and it's also in one of the articles that we published by Belinda and [INAUDIBLE]. And Belinda also talks about how people often make fun of gringos, but making fun is a relationship, is a way of engaging, of liking them, of acknowledging them. So even make fun or tease one another can be a way of connecting.

And I appreciate what you said, and I think it's in tune with what we're trying to do, which is to rewrite these mainstream narratives and to replace Indigenous people at the forefront of this field. And so also, that's to the question of if that's presumptuous.

I think, of course, I'm talking a lot to the field of psychedelics, but I do feel that Indigenous people, often they appear as footnotes or in the intro-- psilocybin research, the Aztec used always. It's like, wait, wait, wait, wait. You are coming after the Aztec. Wait, wait, wait, you are coming after Maria Sabina. And it's just a kind of what is the center and what is the back, kind of change the perspective on that. And so I think you got what I wanted to do here. And I think that's what we need to do to start reconciling a bit colonial encounters.

CHARLES STANG: Well, maybe let me close by saying we have here on the icon, the Center for the Study of World Religions, and I'm very proud to direct this center, but the category of world religions has served at times to render invisible Indigenous traditions because they are not afforded a place in the category of world religions often. Certainly traditionally, they're not.

So to redress that, we have had a very lively animist reading group at the center. In fact, the animist group has inspired a number of invitations including Robin Wall Kimmerer several years ago now. So that's been a particular challenge to me is to find ways to incorporate religious traditions that are labeled for better or for worse, Indigenous, animist, and shamanic. And all of those labels are things I'm deeply interested in and would like to press further on, indigeneity, animism, and shamanism.

BIA LABATE: And that's not just theoretical because you take the case of ayahuasca in the United States, you have the Christian syncretic Brazilian religion [INAUDIBLE] your own division now, which I also thought about talking about this. It's a whole thing. They have permission from the state to use ayahuasca not considered religions that are legitimate because they are Christian, and they are-- the Religious Restoration Freedom Act doesn't really have a definition of religion.

And religion has been decided by courts in different cases and have often been mirrored after the big world monotheistic religions such as Christianity and Judaism and Islam, and other forms of religiosity, minor or Indigenous-based spiritualities, have not gained the legal status of religion.

They therefore are pathologized and criminalized and stigmatized, which is all the case of the shamanic uses of ayahuasca, which just leads me to also invite folks to donate to our crowdfunding campaign that we're currently doing in support of the Church of the Eagle and the Condor Religious Freedom Initiative.

We're trying to get a FOIA request to ask the government. The government has apprehended over 80 batches of ayahuasca during pandemic, and this has been aggressive to the communities, and people are tired of this illegality. So yeah, the conversation on religion is not just conceptual and a thing for a nice cup of tea among scholars, but it's actually influential whether you get to sent to prison or not in the case of psychedelics.

And also, peyote has been the discussion is very racialized on whether it's a federal tribe or nonfederal or non-Indigenous. Are those users legitimate or not? So all of these conversations have a lot of implications. And this is also a different angle that maybe you can pursue in the future in your series.

CHARLES STANG: Well, I'll no doubt be asking your advice about the future of this series. And maybe it's also worth noting that, depending on how you label and count, but it's not at all clear to me that Indigenous, shamanic, and animist traditions are a minority in any way globally. They could very well be the global majority.

BIA LABATE: Exactly. True.

CHARLES STANG: So Bia, let me thank you one last time for this amazing lecture, and thank you for your time and your talents. And I promise you I will be following up with questions because this series probably almost certainly will not end this year. We're going to carry it forward next year, perhaps even beyond that. So there's many more iterations of this conversation we need to have.

For those of you who are still with us, the next conversation will have is on March 22, as I mentioned, and with that, we'll be returning to the theme of psychedelics in the ancient Mediterranean with the so-called Mithras Liturgy from Greco-Roman Egypt. Excuse me.